The Unconquered Sun

Generously supported by Burrinja Cultural Centre

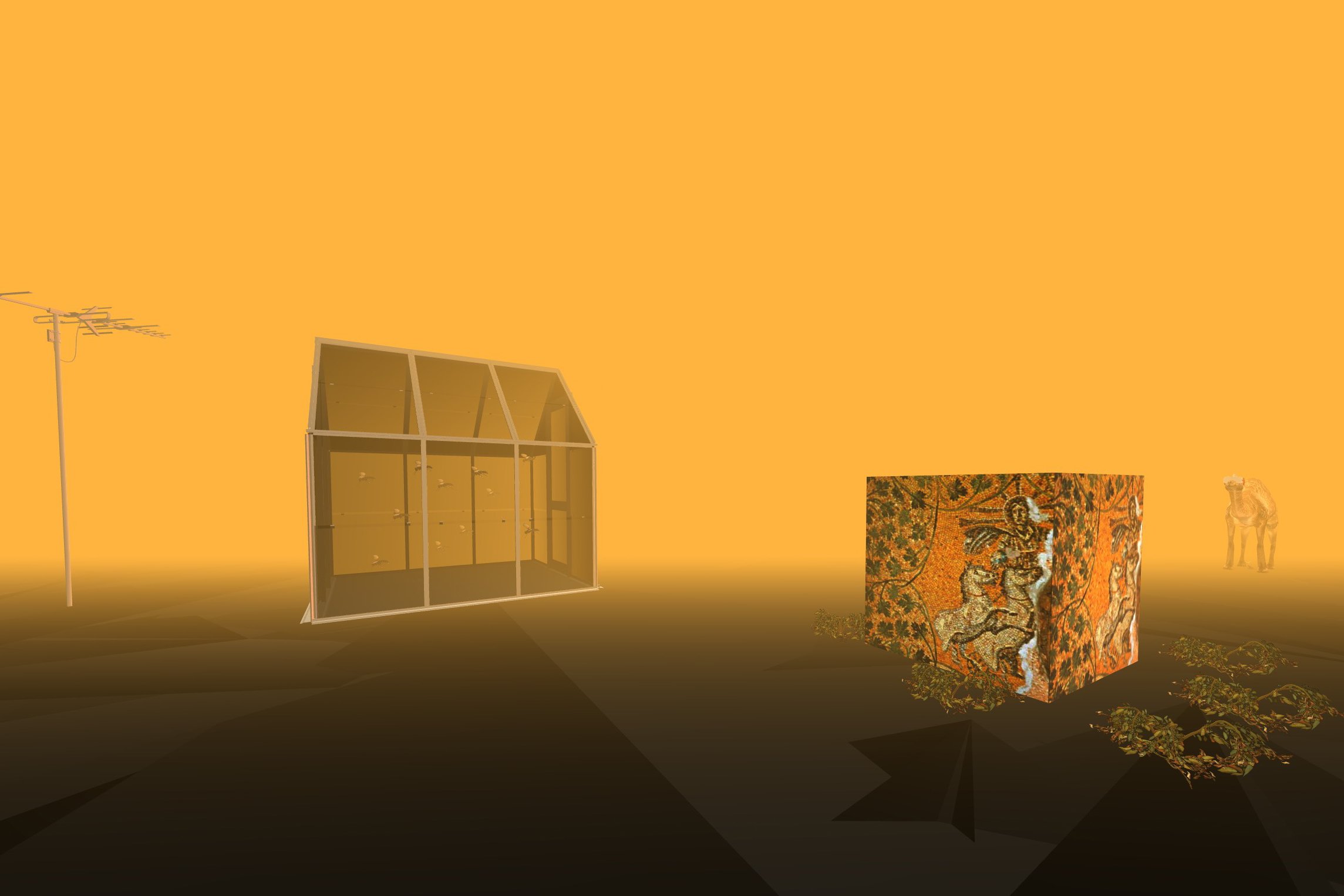

The Unconquered Sun is a virtual reality climate dystopia commissioned by Burrinja Cultural Centre for Holding Pattern, Between Here and Tomorrow. Drawing on surrealism, food security science, and the cult of Sol Invictus from the Roman Empire, it explores humanity’s potential future relationship with the sun. The Unconquered Sun utilises future archaeology, with clues such as failed crops, satellite dishes, and solar monuments scattered across the scene. These artefacts allude to mysterious practices and attempts to cultivate the landscape before its abandonment.

The clouded, orange desert mimics the global aridity processes currently underway on Earth, where rising greenhouse gas emissions have driven long-term water and climate-based issues that affect both human society and natural ecosystems (Chai et al., 2021). Coldrey questions our dependent relationship with the sun in the context of this accelerating anthropogenic change. The sun is a giver of life in Earth’s, compelling Earth’s early evolutionary history from bacteria and insects to birds and mammals. However, the sun can also be a taker of life, begging the question, how might our future mythologies of the sun evolve around a climate catastrophe?

The sun was once thought to be the centre of the universe in medieval astronomy, even receiving God status in the Roman Empire. Perhaps sun cults may re-emerge, reintroducing reverence and respect for the sun in a final, desperate attempt to continue life on Earth. Coldrey’s landscape features two low-tech sun monuments, including a reference to pre-industrial sun mythology, with the golden replica of the Mosaic of Sol in Mausoleum M in the Vatican Necropolis, dated back to the 3rd century AD.

Two primary food sources are present in the landscape of the Unconquered Sun; potato crops and cultivated greenhouses of solider flies. Alongside climate adaption measures, some academics argue that the potato is a viable climate-smart crop, perhaps one of few crops benefiting from larger yields in global warming scenarios (Jennings et al. 2020). Others argue that this change will lead to more diseases in potato crops, raising the question of what foods’ tipping point will be. Could super crops be enough to ensure food security in extreme aridity scenarios?

Another option is using controlled environments for crop growth, but how might this play out in resource-poor settings? Tzachor, Richards and Holt (2021) suggest that risk resilient future diets could include insect larvae from solider flies and mealworms in enclosed environments for both human food and livestock feed. Coldrey references these possibilities with the absurd fusion of desert greenhouses and giant insects, accompanied by a lone camel that stands idly by. This camel symbolises water scarcity, isolation, and existential dread, wearing its own virtual reality headset while presumably dreaming of somewhere new, old, or elsewhere entirely. This distraction could even be an emerging form of animal ethics, facilitating oblivion from a starved, sun-scorched landscape beyond repair.